Studies reveal: When you mess with native forests, they become more flammable. Commercial logging of moist native forests creates conditions that increase the severity and frequency of bushfires. Is it simply a coincidence, that the province which has the highest rates of deforestation, is suffering from the worst forest fires in our country? Pine beetle devastation - we often hear climate change, but not a word about their predators' (woodpecker) population decline due to logging.

In the summer of 2017, there were over 1 million hectares of land burned, over 60,000 people evacuated, and half a billion dollars spent for fire suppression. This year, it has gotten out of control again, wrecking havoc on land and making it hard for us to breathe at times. British Columbia has the largest forestry industry in Canada, and now it is paying the price. To speak truthfully, yes, there has always been forest fires every year. But what has been causing them to worsen over the years? This is what we will explore. The corporate-owned media is quick to point the finger at global warming, causing our heads to turn away from any other causes, such as industrial practices. An investigation by The Narwhal shows that since 2012, the year the federal government formally designated whitebark pine as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, more than 19,000 cubic metres of the trees have been logged in B.C. If those trees were telephone poles, they would string a line from Vancouver nearly 800 kilometres north to Prince George.

Imagine a Forest

Imagine this: one to three hundred years ago, a natural untouched forest, with hundreds of millions of enormous trees, whose roots held in large amounts of moisture in the ground. At nightfall, water vapor fills the air, forming a natural fog, while the trees and vegetation release their moisture via evapotranspiration. The whole forest is wet and humid, with the natural vegetation that surrounds it, and the moss that grows on the tree, thriving in the humid environment. How likely is a fire to start here?

Imagine this: one to three hundred years ago, a natural untouched forest, with hundreds of millions of enormous trees, whose roots held in large amounts of moisture in the ground. At nightfall, water vapor fills the air, forming a natural fog, while the trees and vegetation release their moisture via evapotranspiration. The whole forest is wet and humid, with the natural vegetation that surrounds it, and the moss that grows on the tree, thriving in the humid environment. How likely is a fire to start here?Now, fast forward to three hundred years later, where the logging industry is cutting down billions of trees each year, milling and exporting Canadian lumber in vast amounts. Roads are paved through the forests to allow lumber trucks to pass, while the forest is losing its trees in many areas, causing the ground to eventually dry up over the years - many unwanted trees simply left uprooted, only to dry out and act as tinder for fire. Trees are replanted each year, but not enough to replace the lost trees, and not even close to their age and size.

All these trees, for many years, are what kept the ground moist, creating microclimates within the forest, preventing massive fires - now, they are uprooted in millions each year, creating dry pockets, as the dry ground becomes more prone to fire. Keep this term, dry pockets, in mind, because you will be seeing it a lot. It's the same problem, anywhere you go in the world, whether it be the Amazon, China, or Russia, where the chopping down of trees has become the norm. Welcome to the world of deforestation.

|

| A simple Google image search: Deforestation before and after |

There have been a number of studies done on the relationship between deforestation and forest fires. They all seem to conclude the same thing: deforestation is causing our forests to become more prone to wildfires. Here's what an interesting study entitled, Effects of logging on fire regimes in moist forests, has to say on the topic:

Logging can change forests in at least five interrelated ways that could influence wildfire frequency, extent and/or severity. These include changing: (1) microclimates,(2) stand structure and species composition, (3) fuel characteristics, (4) the prevalence of ignition points, and (5) patterns of landscape cover.

Do you recall us discussing the old forests and their microclimates that have changed over the years? Here is what another study has to say on the topic, entitled, Logging makes forests more flammable:

|

There was also an interesting study done in the central region of the Brazilian Amazon. For simplicity's sake, we have pulled out some important information. In this study, entitled, Deforestation-Induced Fragmentation Increases Forest Fire Occurrence in Central Brazilian Amazonia, it states:

Forest edges resulting from landscape fragmentation are highly fire-prone due to increased

dryness, higher fuel load compared to forest interior and proximity to ignition sources from adjacent

management areas. Fragmentation and its resulting edge effects may act synergistically

with the ongoing large-scale changes in climate and fire regimes, threatening the Amazonian forest

ecological integrity... Fire density (FD) increased with habitat loss (HL), with greater variability in the higher levels of deforestation ... About 95% of active fires and the most intense ones (FRP > 500 megawatts) were found in the first kilometre from the edges in forest areas [dry pockets] ...We conclude that the susceptibility of the landscape to forest fires increases at the beginning of the deforestation process.

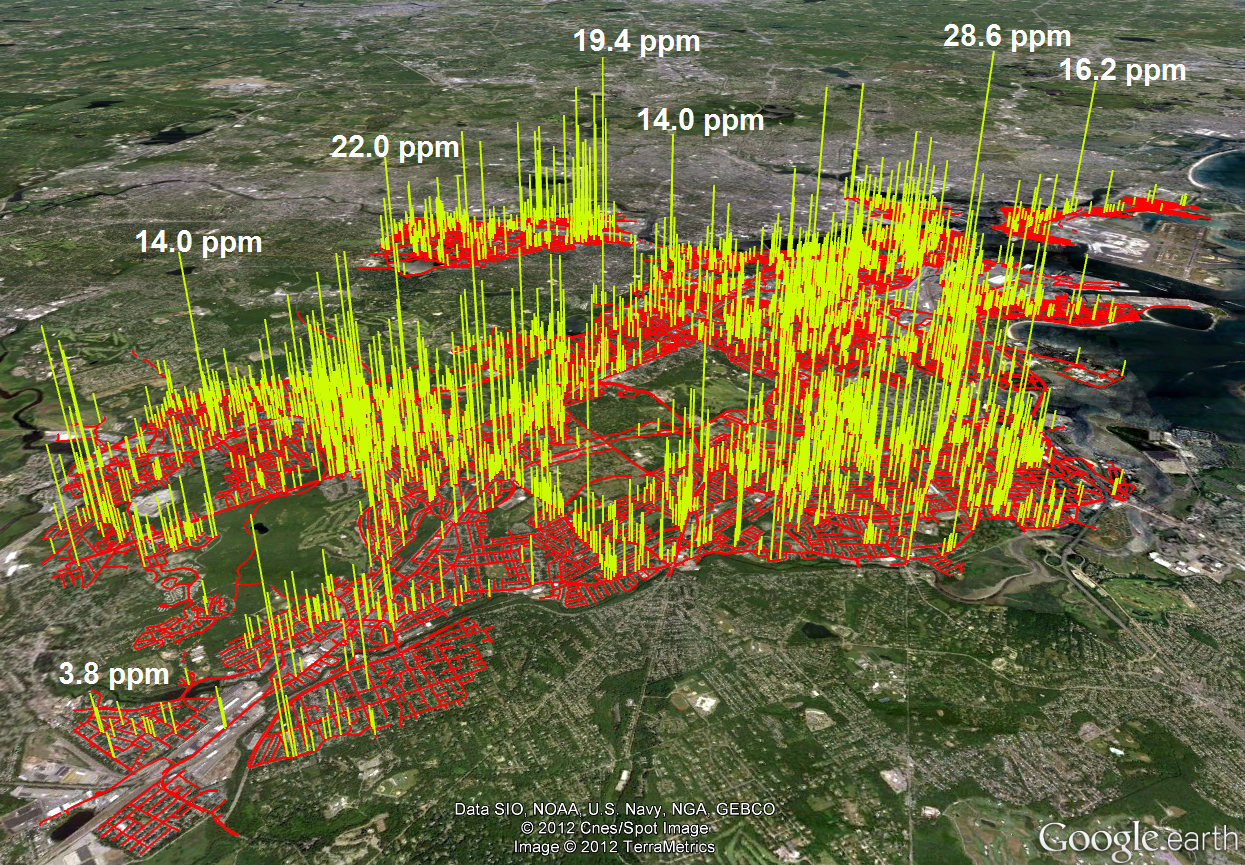

In other words, from a study done in the Amazon, we learned that majority of the active fires and the most intense ones, were found within the first kilometre from the edges of deforested areas, close to those dry pockets. Now, let's do a simple Google image search of "BC fires bird's eye view" and compare the results below. Notice how close these fires are to the edge of deforested areas [dry pockets], where yearly logging has increased ground dryness.

Now people might be thinking, yes, but that study was done in Amazon, and here we are talking about British Columbia, Canada. But, wait a minute. If deforestation is causing wildfires in a much more wet area that receives up to 9,000 mm of rain each year, as compared to a few hundred mm of rainfall in BC, imagine how much more important this study is for drier areas. In other words, if deforestation is causing increasing wildfires in rainforest areas like the Amazon, imagine the havoc that deforestation would be causing in much drier areas, like Canada.

The Pine Beetle Connection

The issue of pine beetles is not so black and white - it involves a complex ecosystem of various trees and their resin defenses, climate, and natural predators of the pine beetle. The main predator of the pine beetle is the woodpecker, and as anyone could guess, their population has been steadily declining, due to habitat loss and destruction by the lumber industry. Simply put, less woodpeckers means more pine beetles. Williamson's sapsucker is listed as an endangered species in B.C. with only about 400 pairs remaining. Now you could just guess why the Lewis's woodpecker population is at risk, and we can expect more species decline to come in the near future if logging continues the way it has been going.

The issue of pine beetles is not so black and white - it involves a complex ecosystem of various trees and their resin defenses, climate, and natural predators of the pine beetle. The main predator of the pine beetle is the woodpecker, and as anyone could guess, their population has been steadily declining, due to habitat loss and destruction by the lumber industry. Simply put, less woodpeckers means more pine beetles. Williamson's sapsucker is listed as an endangered species in B.C. with only about 400 pairs remaining. Now you could just guess why the Lewis's woodpecker population is at risk, and we can expect more species decline to come in the near future if logging continues the way it has been going.

The main threat to bird species in the mountains hasn’t been crowds of weekend gawkers. It’s tended to be smaller groups, mostly riding bulldozers and packing chainsaws. The logging industry has left its deadly mark on local wildlife habitat. Far too many river valleys in southwest mainland BC have had a logging road punched to the back of the watershed, with its forest cloak ripped to tatters by clearcut logging. The decline of woodpeckers is largely due to logging of cast areas of woodland as well as their conversion to farmland has been the major cause of range contractions, regional extinctions, and population declines both now and historically. Some trees dispersal even relies on such birds. For example, Pinus albicaulis or whitebark pine is a slow-growing, five-needled pine tree generally found at higher elevations. One bird species, the Clark’s Nutcracker, is responsible for the natural dispersal of its seeds. This bird feeds on the seeds from the tree’s egg-shaped, purple cones. As colder weather approaches, it flies away with the seeds and buries them in small caches, typically within a couple of kilometres of the cones it has harvested, but sometimes more than 30 kilometres away.

Woodpeckers on the Decline

Woodpeckers use a lot of energy scaling bark from trees to reach beetle larvae. As well as devouring beetle larvae directly, three-toed woodpeckers indirectly kill beetle broods when searching tree trunks for food. A Swiss study estimates the number of bark beetles devoured at all stages of development (from larva and pupa to beetle) at approximately 670,000 per year and per woodpecker, meaning that Switzerland’s entire population of three-toed woodpeckers eats an estimated 1.7 billion bark beetles per year. If these birds find a tree that offers plenty of food, the bird can strip the bark off of virtually the entire tree in a short space of time. This exposes the beetle broods to adverse weather and they die from dehydration or unfavorable temperatures, for example. Fungi also infest breeding galleries. Bark beetle broods in sections of bark that have fallen to the ground are in turn prey for other birds or small mammals. When bark is thinner owing to sections being stripped away, this can trigger increased parasitisation of bark beetle larvae. In this case, parasitic wasps with short ovipositor are able to parasitise the larvae beneath the bark, which they would not be able to reach under normal, thicker bark. This indirect destruction of bark beetles brought about by three-toed woodpeckers bark scaling is more considerable than direct consumption. Three-toed woodpeckers can therefore play a key role in controlling bark beetle populations in forests dominated by conifers.

Woodpeckers use a lot of energy scaling bark from trees to reach beetle larvae. As well as devouring beetle larvae directly, three-toed woodpeckers indirectly kill beetle broods when searching tree trunks for food. A Swiss study estimates the number of bark beetles devoured at all stages of development (from larva and pupa to beetle) at approximately 670,000 per year and per woodpecker, meaning that Switzerland’s entire population of three-toed woodpeckers eats an estimated 1.7 billion bark beetles per year. If these birds find a tree that offers plenty of food, the bird can strip the bark off of virtually the entire tree in a short space of time. This exposes the beetle broods to adverse weather and they die from dehydration or unfavorable temperatures, for example. Fungi also infest breeding galleries. Bark beetle broods in sections of bark that have fallen to the ground are in turn prey for other birds or small mammals. When bark is thinner owing to sections being stripped away, this can trigger increased parasitisation of bark beetle larvae. In this case, parasitic wasps with short ovipositor are able to parasitise the larvae beneath the bark, which they would not be able to reach under normal, thicker bark. This indirect destruction of bark beetles brought about by three-toed woodpeckers bark scaling is more considerable than direct consumption. Three-toed woodpeckers can therefore play a key role in controlling bark beetle populations in forests dominated by conifers.

Moisture Affects Tree Resin Production

Many coniferous trees defend themselves against mountain pine beetle attacks with toxic resin. Low or endemic beetle populations cannot overcome the defenses of healthy trees and attack suppressed, weak or dying trees. According to Vité (1961), "the deficiency of water or rapid transpiration decreases the turgid pressure inside the epithelial cells lining resin ducts, which in turn decreases the pressure inside the resin ducts and the amount of oleoresin produced." In other words, less water means less tree resin being produced.

Many coniferous trees defend themselves against mountain pine beetle attacks with toxic resin. Low or endemic beetle populations cannot overcome the defenses of healthy trees and attack suppressed, weak or dying trees. According to Vité (1961), "the deficiency of water or rapid transpiration decreases the turgid pressure inside the epithelial cells lining resin ducts, which in turn decreases the pressure inside the resin ducts and the amount of oleoresin produced." In other words, less water means less tree resin being produced.

The Pine Beetle Connection

The issue of pine beetles is not so black and white - it involves a complex ecosystem of various trees and their resin defenses, climate, and natural predators of the pine beetle. The main predator of the pine beetle is the woodpecker, and as anyone could guess, their population has been steadily declining, due to habitat loss and destruction by the lumber industry. Simply put, less woodpeckers means more pine beetles. Williamson's sapsucker is listed as an endangered species in B.C. with only about 400 pairs remaining. Now you could just guess why the Lewis's woodpecker population is at risk, and we can expect more species decline to come in the near future if logging continues the way it has been going.

The issue of pine beetles is not so black and white - it involves a complex ecosystem of various trees and their resin defenses, climate, and natural predators of the pine beetle. The main predator of the pine beetle is the woodpecker, and as anyone could guess, their population has been steadily declining, due to habitat loss and destruction by the lumber industry. Simply put, less woodpeckers means more pine beetles. Williamson's sapsucker is listed as an endangered species in B.C. with only about 400 pairs remaining. Now you could just guess why the Lewis's woodpecker population is at risk, and we can expect more species decline to come in the near future if logging continues the way it has been going.The main threat to bird species in the mountains hasn’t been crowds of weekend gawkers. It’s tended to be smaller groups, mostly riding bulldozers and packing chainsaws. The logging industry has left its deadly mark on local wildlife habitat. Far too many river valleys in southwest mainland BC have had a logging road punched to the back of the watershed, with its forest cloak ripped to tatters by clearcut logging. The decline of woodpeckers is largely due to logging of cast areas of woodland as well as their conversion to farmland has been the major cause of range contractions, regional extinctions, and population declines both now and historically. Some trees dispersal even relies on such birds. For example, Pinus albicaulis or whitebark pine is a slow-growing, five-needled pine tree generally found at higher elevations. One bird species, the Clark’s Nutcracker, is responsible for the natural dispersal of its seeds. This bird feeds on the seeds from the tree’s egg-shaped, purple cones. As colder weather approaches, it flies away with the seeds and buries them in small caches, typically within a couple of kilometres of the cones it has harvested, but sometimes more than 30 kilometres away.

Woodpeckers on the Decline

Woodpeckers use a lot of energy scaling bark from trees to reach beetle larvae. As well as devouring beetle larvae directly, three-toed woodpeckers indirectly kill beetle broods when searching tree trunks for food. A Swiss study estimates the number of bark beetles devoured at all stages of development (from larva and pupa to beetle) at approximately 670,000 per year and per woodpecker, meaning that Switzerland’s entire population of three-toed woodpeckers eats an estimated 1.7 billion bark beetles per year. If these birds find a tree that offers plenty of food, the bird can strip the bark off of virtually the entire tree in a short space of time. This exposes the beetle broods to adverse weather and they die from dehydration or unfavorable temperatures, for example. Fungi also infest breeding galleries. Bark beetle broods in sections of bark that have fallen to the ground are in turn prey for other birds or small mammals. When bark is thinner owing to sections being stripped away, this can trigger increased parasitisation of bark beetle larvae. In this case, parasitic wasps with short ovipositor are able to parasitise the larvae beneath the bark, which they would not be able to reach under normal, thicker bark. This indirect destruction of bark beetles brought about by three-toed woodpeckers bark scaling is more considerable than direct consumption. Three-toed woodpeckers can therefore play a key role in controlling bark beetle populations in forests dominated by conifers.

Woodpeckers use a lot of energy scaling bark from trees to reach beetle larvae. As well as devouring beetle larvae directly, three-toed woodpeckers indirectly kill beetle broods when searching tree trunks for food. A Swiss study estimates the number of bark beetles devoured at all stages of development (from larva and pupa to beetle) at approximately 670,000 per year and per woodpecker, meaning that Switzerland’s entire population of three-toed woodpeckers eats an estimated 1.7 billion bark beetles per year. If these birds find a tree that offers plenty of food, the bird can strip the bark off of virtually the entire tree in a short space of time. This exposes the beetle broods to adverse weather and they die from dehydration or unfavorable temperatures, for example. Fungi also infest breeding galleries. Bark beetle broods in sections of bark that have fallen to the ground are in turn prey for other birds or small mammals. When bark is thinner owing to sections being stripped away, this can trigger increased parasitisation of bark beetle larvae. In this case, parasitic wasps with short ovipositor are able to parasitise the larvae beneath the bark, which they would not be able to reach under normal, thicker bark. This indirect destruction of bark beetles brought about by three-toed woodpeckers bark scaling is more considerable than direct consumption. Three-toed woodpeckers can therefore play a key role in controlling bark beetle populations in forests dominated by conifers.Moisture Affects Tree Resin Production

Many coniferous trees defend themselves against mountain pine beetle attacks with toxic resin. Low or endemic beetle populations cannot overcome the defenses of healthy trees and attack suppressed, weak or dying trees. According to Vité (1961), "the deficiency of water or rapid transpiration decreases the turgid pressure inside the epithelial cells lining resin ducts, which in turn decreases the pressure inside the resin ducts and the amount of oleoresin produced." In other words, less water means less tree resin being produced.

Many coniferous trees defend themselves against mountain pine beetle attacks with toxic resin. Low or endemic beetle populations cannot overcome the defenses of healthy trees and attack suppressed, weak or dying trees. According to Vité (1961), "the deficiency of water or rapid transpiration decreases the turgid pressure inside the epithelial cells lining resin ducts, which in turn decreases the pressure inside the resin ducts and the amount of oleoresin produced." In other words, less water means less tree resin being produced.Conclusion

Loss of of natural vegetation and trees, and wetness of the forest floor is causing our ground in certain areas of the forest to dry out and become more prone to fire. We have cherry-picked and biased studies put out by the logging industry in an attempt to prove that logging does not affect birds and their populations, along with other environmental destruction - all done in order to allow the logging industry to continue wrecking havoc in our beautiful forests.

The media will have people yapping about global warming, temperature changes, pine beetles, people not putting out their cigars, and record-breaking heat-waves - but not a single mention of lumber industry practices or deforestation, and their effects on avian predators of pine beetles or bushfires and forest health. What has the continuous logging over the many years done to the vegetation, tree-pests, micro-climate, humidity, and ground of our forests? Think about it.

The media will have people yapping about global warming, temperature changes, pine beetles, people not putting out their cigars, and record-breaking heat-waves - but not a single mention of lumber industry practices or deforestation, and their effects on avian predators of pine beetles or bushfires and forest health. What has the continuous logging over the many years done to the vegetation, tree-pests, micro-climate, humidity, and ground of our forests? Think about it.

|

| Do we really need a study to tell us this? Just take a walk in the forest and feel the difference in how these trees cool the climate when compared to an urbanized concrete built city. The study can be read here. |

|

|

| Something to be proud of? How many of those ancient giant trees did they cut down? |

|

| Check out that dry pocket! If that's not tinder for fire, then what is? |

|

| Current map of fires in BC - Aug 22, 2018. Is it a coincidence that the province which has the highest rates of deforestation is suffering from the worst forest fires in Canada? |

|

| Imagine how much moisture these giant trees held in the forest. Oh no problem, we'll just replant some tiny trees! |

|

| A perfect recipe for fire: Logging roads and deforested dry pockets. |

|

| The media that is owned by our industries and corporations: blame the heatwave, not the logging industry. |

|

| Do you see the lumber roads and dry pockets? |

|

| Agriculture also affects our forests. Just imagine how much moisture and shade those trees provide. |

|

| The studies have been nailing this topic for years now. All right, time to pay a bunch of scientists to put out studies to conclude that logging is good for the forest fires now. |